A new academic study has uncovered alarming security flaws and deceptive practices among some of the world's most downloaded VPN apps, collectively impacting over 700 million Android users.

The research reveals that dozens of popular VPN services, often marketed as independent and secure, are secretly connected through shared ownership, server infrastructure, and even cryptographic credentials, exposing user traffic to surveillance and decryption.

The paper was authored by Benjamin Mixon-Baca (ASU/Breakpointing Bad), Jeffrey Knockel (Citizen Lab/Bowdoin College), and Jedidiah R. Crandall (Arizona State University) and presented at the Free and Open Communications on the Internet (FOCI) 2025 conference. Through a combination of APK analysis, business record investigation, and network forensics, the researchers identified three distinct families of VPN providers that obfuscate their corporate ownership and introduce significant security risks.

Obscured ownership and shared infrastructure

The study began by examining the 100 most-downloaded VPN apps from SensorTower and AppMagic, narrowing the list to 50 non-US providers, many claiming to operate from Singapore, a known hotspot for shell VPN firms. Using APK decompilation, business filings from OpenCorporates, and forensic traces from shared libraries and cryptographic keys, the authors identified 21 apps linked to 13 providers, which they clustered into three families, labeled A, B, and C.

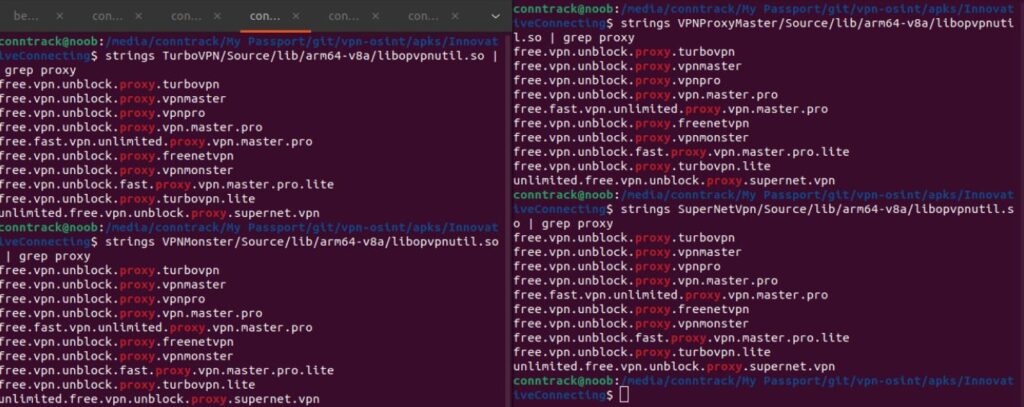

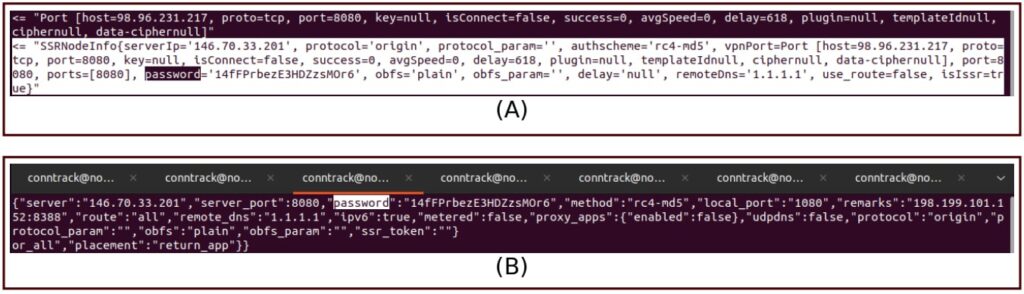

Family A includes providers such as Innovative Connecting, Autumn Breeze, and Lemon Clove, responsible for apps like TurboVPN, VPN Proxy Master, and Snap VPN, each with tens or hundreds of millions of downloads. These apps exhibit striking code similarities and embed identical shared libraries like libopvpnutils.so. All of them were found to hard-code the same Shadowsocks passwords within their APKs, stored in files such as server_offline.ser and encrypted with AES-192-ECB.

Family B, comprised of Matrix Mobile, Wildlook Tech, and others, was linked through identical shared libraries (libcore.so), common VPN server IPs, and 14 hardcoded passwords. Although codebases varied slightly more than Family A, they too reused server infrastructure and encrypted configuration files with predictable logic.

Family C, which includes Free Connected Limited (developer of X-VPN) and Fast Potato Pte. Ltd., used a proprietary tunneling protocol disguised on port 53 (normally used for DNS). These apps shared rare native libraries and even identical variable names (like psk for pre-shared keys), further suggesting common authorship.

Critical security flaws

The researchers uncovered multiple overlapping vulnerabilities in these apps, several of which completely undermine the confidentiality VPNs claim to provide:

Hard-coded Shadowsocks passwords: In both Families A and B, attackers could extract these symmetric encryption keys and use them to decrypt user traffic. Because the same password is used across all clients, one key can compromise millions of users.

Deprecated ciphers: Several apps still use RC4-MD5 for Shadowsocks, a cipher suite known to be insecure and deprecated since 2020. No key discard or IV protection was implemented, making traffic potentially susceptible to confirmation or even key recovery attacks.

Blind on-path attacks: All three families' apps are vulnerable to client-side inference attacks, allowing adversaries on the same network (e.g., Wi-Fi) to infer active connections despite VPN tunnel encryption. This was due to the misuse of libraries like libredsocks.so, which improperly interact with Android's connection tracking framework.

Invasive telemetry: Some apps silently queried location-related data such as ZIP codes via ip-api.com, and uploaded it to Firebase servers, in violation of their own privacy policies, which claim not to collect address-level data.

Links to China

The study builds on previous investigations by the Tech Transparency Project, which had linked apps like TurboVPN and Snap VPN to Chinese firm Qihoo 360, a company sanctioned by the US government for connections to the People's Liberation Army (PLA). While these apps state they are operated from Singapore, business filings revealed addresses in China and ownership by Chinese nationals, directly contradicting their public claims.

The researchers also confirmed infrastructure sharing by using extracted Shadowsocks credentials from one app to successfully connect to the VPN servers of a supposedly different provider, demonstrating cross-app access and “freeloading” potential.

This study delivers one of the most comprehensive forensic analyses of mobile VPN apps to date, revealing how scale, obscurity, and security failures collide to place millions of users at risk. If you're looking for trustworthy VPN products, check out our list of the best no-logs VPNs that have passed third-party audits.

Leave a Reply