A new website, Is It Really FOSS?, aims to bring much-needed clarity to the murky world of open source software distribution.

Launched by UK-based developer Dan Brown, the platform evaluates whether software projects marketed as “open source” genuinely meet the standards of Free and Open Source Software (FOSS), or if they're leveraging the label without delivering on its promises.

The site builds on Brown's earlier initiative, Open Source Confusion Cases, which chronicled misrepresentation in open source licensing. However, this new effort takes a more balanced and systematic approach. Instead of focusing solely on problematic cases, Is It Really FOSS? also highlights projects that exemplify strong adherence to FOSS principles. The reviews are presented in an accessible, categorized format, designed for both developers and decision-makers evaluating software for personal use or enterprise integration.

Projects are classified across five categories, ranging from fully FOSS to proprietary software marketed as open source, based on factors like license clarity, server-side transparency, and marketing honesty. The goal is to help users make better-informed decisions and spot potential pitfalls in a software project's licensing or distribution model before committing to it.

Why open source matters

While the label “open source” once implied trust, community, and user freedom, today it is often diluted. Some projects advertise themselves as FOSS while quietly introducing closed-source components, complex licensing agreements, or backend restrictions that hinder user rights. In regulated industries or enterprise environments, these discrepancies can lead to compliance violations or costly vendor lock-in.

Understanding whether a project is really FOSS is no longer a niche concern. It affects system administrators deploying secure infrastructure, developers integrating dependencies, and users who expect transparency from privacy-oriented tools. Ambiguous licensing or open-washing can mask significant limitations or risks, especially when the server-side components remain proprietary or self-hosting is impractical.

How the site works

Is It Really FOSS? targets projects that are publicly visible, widely adopted, and marketed, at least in part, as open source. The reviews are manually compiled and analyzed by volunteers, and the entire platform is itself open source and hosted on Codeberg. Community contributions are welcome, including new submissions, corrections, and site improvements.

Common licensing and transparency issues tracked by the site include:

- Open Washing – Marketing a product as open source while restricting key parts of the code or usage rights.

- Limited Core Model – Offering a stripped-down FOSS version that requires paid upgrades for essential functionality.

- SSO Tax – Charging extra for basic authentication features, such as single sign-on.

- Source Poisoning – Quietly introducing proprietary code into previously open repositories.

- Overly Complex Licensing – Using license terms that are difficult to interpret without legal assistance.

- VC Funding Risks – Projects that change licenses post-investment, betraying early adopters and community contributors.

Case snapshots

CyberInsider briefly examined how Is It Really FOSS? categorizes several high-profile projects. While we have not independently verified the technical accuracy of every detail, the site's assessments appear thoughtful and aligned with broader concerns about transparency in open source:

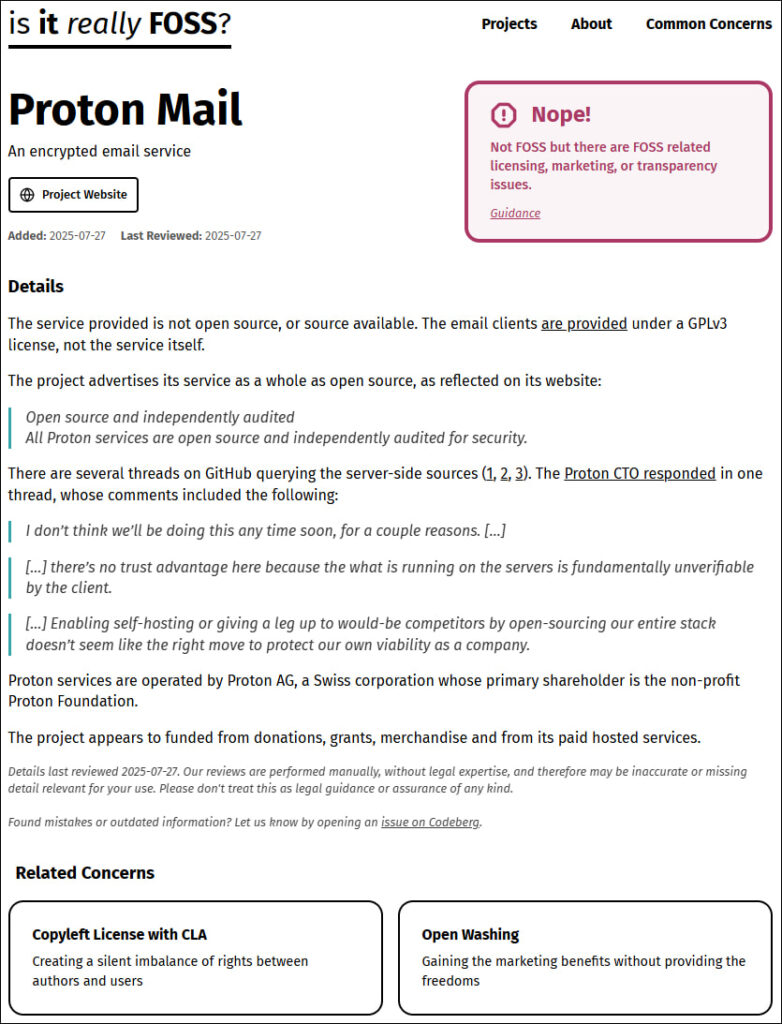

Proton Mail is marked as “Not FOSS with Issues”. While its email clients are licensed under GPLv3, the backend service, which is the core of the platform, is not open source. Despite marketing claims that “all Proton services are open source,” the server code remains proprietary, and the CTO has publicly dismissed plans to open it. This creates a disconnect between public messaging and actual software freedoms.

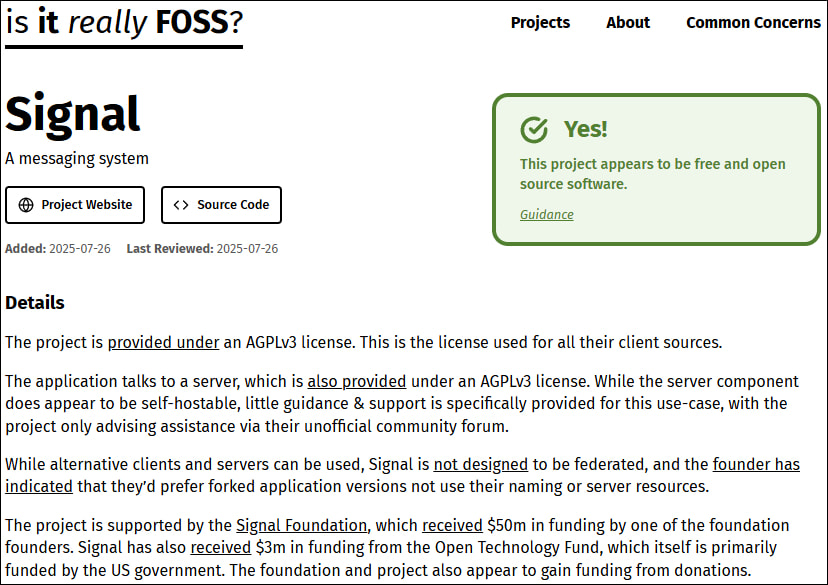

Signal fares better and is labeled “FOSS Project.” Both client and server code are available under the AGPLv3, and although self-hosting is technically possible, it's discouraged and unsupported. Signal's refusal to federate or support forks raises concerns about centralization, but the licensing itself adheres to FOSS principles.

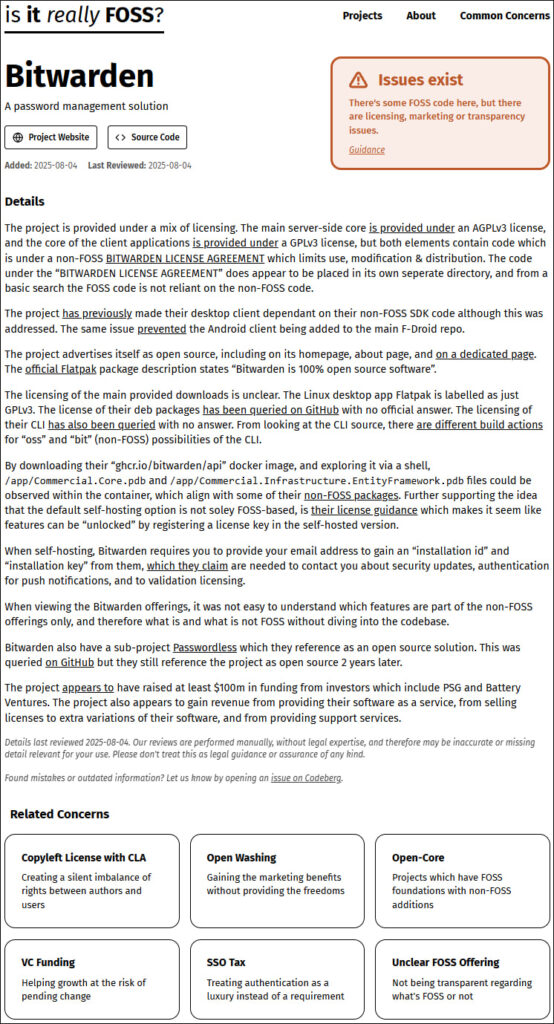

Bitwarden is flagged under “FOSS with Issues.” While parts of the code are licensed under AGPLv3 and GPLv3, certain key components fall under a restrictive proprietary license, complicating self-hosting and transparency. The project's self-identification as “100% open source” conflicts with limitations in practice, such as features locked behind license keys and dependencies on non-FOSS code in official builds.

Each of these cases illustrates why tools like Is It Really FOSS? are becoming essential. The line between open source and proprietary software is no longer clear-cut. For privacy-conscious users, developers, and organizations, understanding what lies behind the “FOSS” label is critical.

While the above is true, it is important to underline that the maintainers of Is It Really FOSS? state that their reviews are not legal opinions. Some assessments may be incomplete, inaccurate, or simply outdated due to the volunteer-based nature of the project. However, the categorization and supporting documentation offer a practical framework for evaluating software claims, especially when those claims influence adoption decisions or compliance processes. All that said, we see Is It Really FOSS? as a good starting point when evaluating software openness.

Leave a Reply