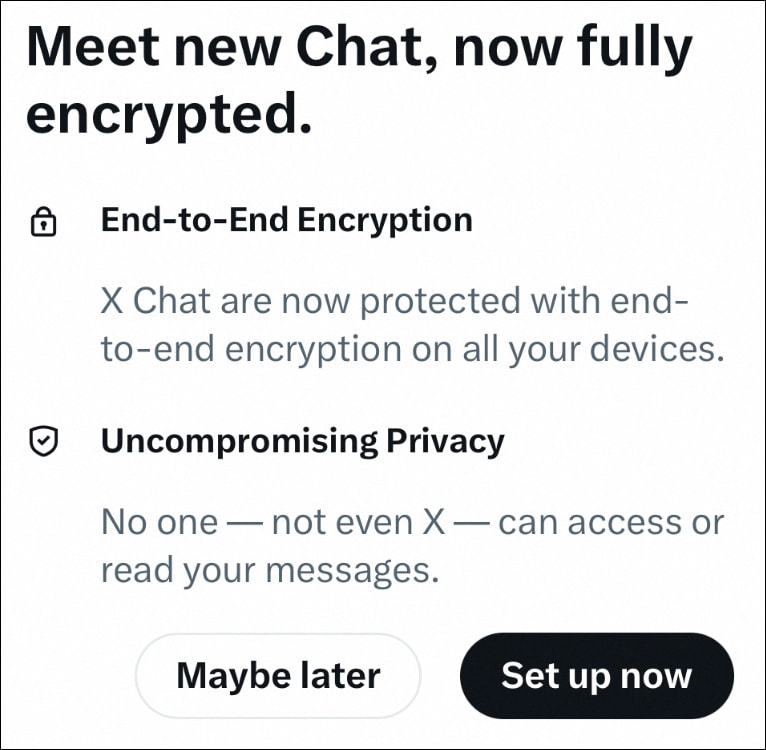

X's encrypted messaging platform, XChat, is now broadly available across mobile and web platforms, but the app's fundamental security model still appears broken.

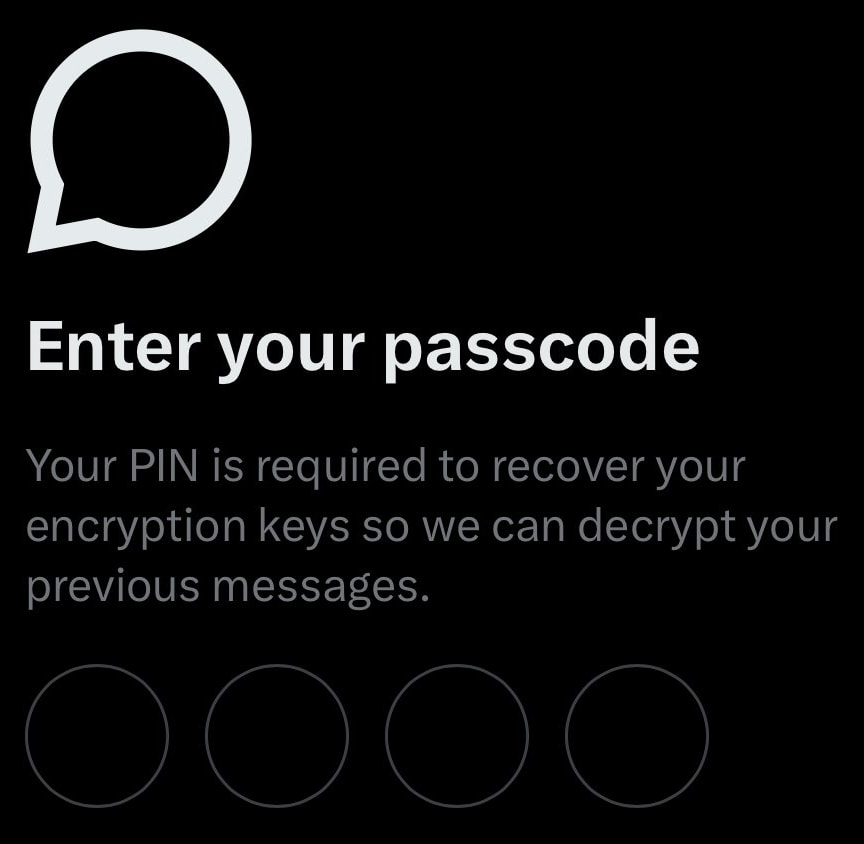

A four-digit PIN used to unlock users' message histories is trivially guessable, raising major concerns about the app's claims of end-to-end encryption (E2EE).

Security researcher and app developer Mysk confirmed that the four-digit PIN allows full message recovery from any device, indicating that the user's private key is stored remotely on X's servers and simply encrypted with the PIN. This effectively turns the PIN into the single gatekeeper of all chat content, a weak barrier with just 10,000 possible combinations.

XChat, first announced in June 2025 by Elon Musk, positions itself as a privacy-forward alternative to messaging apps like Signal and Telegram, boasting features like encrypted group chats, disappearing messages, and support for media and calling, all without requiring a phone number. The system is underpinned by a custom protocol named Juicebox, implemented in Rust and leveraging cryptographic libraries like Libsodium.

Mysk

However, despite these modern components, the way XChat handles key storage undermines its security. Rather than leaving private keys on user devices, which is standard practice for secure messengers, X stores them on its servers. The user's PIN is used to derive a decryption key via Argon2id, a password-hashing function, and then unlock the stored private key. Though Argon2id is memory-hard, the low entropy of a 4-digit PIN means an attacker can brute-force all possible combinations in minutes.

Mysk

Matthew Green, a cryptography professor at Johns Hopkins University, explained that this design trades real end-to-end encryption for convenience. Without hardware-backed protection or verifiable key custody, X employees, or anyone who gains backend access, could decrypt user messages. “If we judge XChat as an end-to-end encryption scheme,” Green writes, “this seems like a pretty game-over type of vulnerability.”

X claims that private keys are distributed across multiple “Juicebox realms,” a form of secret-sharing architecture. Yet research from Juicebox's original protocol designer, Nora Trapp, suggests these realms are all software-based and run solely by X. While some endpoints appear to use code intended for hardware security modules (HSMs), there's no evidence they are deployed in secure environments, nor any published audit or key ceremony to prove otherwise.

To put this in context: while Signal's PIN system allows account recovery and contact restoration, it does not restore messages. Signal also uses hardware-backed security and rate-limited, distributed trust models that make large-scale brute-forcing infeasible. In contrast, XChat's model allows full message recovery with a PIN, stores encryption keys on central servers, and lacks rate-limiting protections or out-of-band key verification.

Compounding the concerns, XChat does not offer forward secrecy. If a private key is ever compromised, either through server-side access or brute-force, the attacker can retroactively decrypt all messages associated with that key. Furthermore, there's no support for safety numbers or key fingerprinting, meaning users cannot verify that their communication partner's key hasn't been tampered with by X or an attacker.

Despite these flaws, the rollout of XChat continues, now available to any user meeting eligibility requirements such as being on the latest version of the app and having interacted with the intended recipient before. The platform supports encrypted messaging for individual and group chats, files, and media, though metadata such as timestamps and recipient IDs remains unencrypted.

Leave a Reply