A catastrophic operational security failure inside the U.S. government has exposed the fragility of digital communication hygiene at the highest levels of power.

Members of the Trump administration’s national security team used the encrypted messaging app Signal to coordinate a military strike on Yemen — and mistakenly included Atlantic editor-in-chief Jeffrey Goldberg in the conversation.

The error revealed not a flaw in the app itself, but a gross misapplication of secure communication practices, where classified military plans were casually disseminated over personal smartphones via a platform not approved for sensitive government discussions.

Signal misused by U.S. government

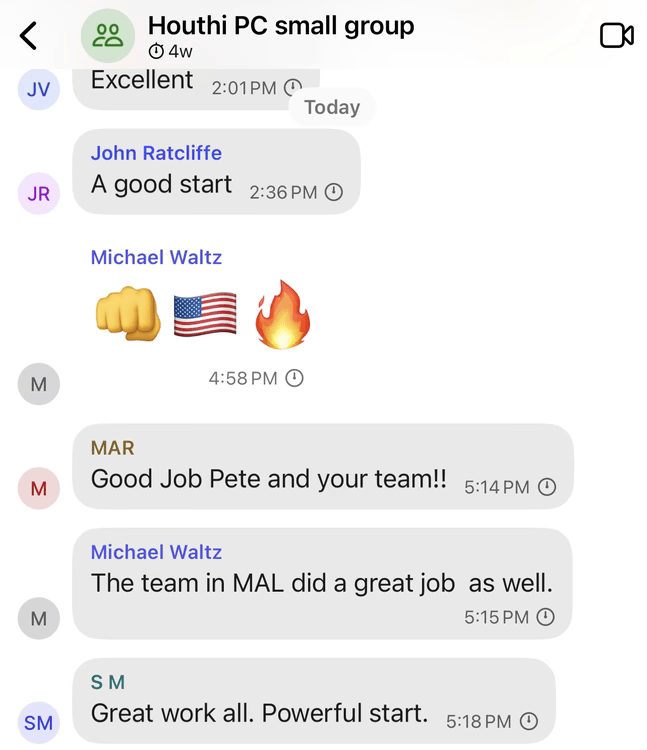

The incident began on March 11, 2025, when Goldberg received a Signal connection request from an account purporting to be Michael Waltz, President Trump’s National Security Adviser. What followed was an invitation to a Signal group chat labeled “Houthi PC small group”, where top U.S. officials, including Vice President JD Vance, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, and Secretary of State Marco Rubio, openly debated the merits and timing of an attack on Houthi positions in Yemen.

Group members exchanged detailed tactical information, including weapons payloads, target locations, and strike timing. These messages were sent and received on commercial smartphones using Signal, which, while end-to-end encrypted, is not authorized for classified communications and cannot substitute for government systems such as SIPRNet or designated SCIF environments.

According to Goldberg’s report, some messages were set to auto-delete within a week, raising potential violations of federal records retention laws. At no point during the multi-day conversation did any official notice Goldberg’s presence in the group — or if they did, they said nothing.

The group continued to operate under the assumption of security, with messages such as “We are currently clean on OPSEC” being posted, despite the fact that a journalist had full visibility into the planning of the operation. At 11:44 a.m. on March 15, Goldberg received a message from “Pete Hegseth” that detailed the final operation plan, with bombing expected to commence two hours later. At 1:55 p.m., explosions were reported in Sanaa, confirming the authenticity of the leaked operation.

The Atlantic

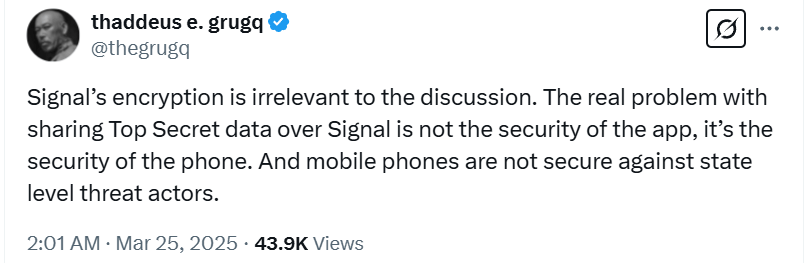

Signal, widely used by journalists and privacy-conscious users, is praised for its encryption protocol and minimal metadata handling. However, it was never designed for handling classified military communications. The app is not cleared for use in any capacity involving national defense information, and its deployment in this context points to a broader cultural lapse in security discipline among senior officials.

The scale of the failure is amplified by the stature of those involved. The “Houthi PC small group” included at least 18 senior figures, from Cabinet-level leaders to National Security Council staff. At least one CIA officer’s name was also shared within the group, though Goldberg withheld it from publication.

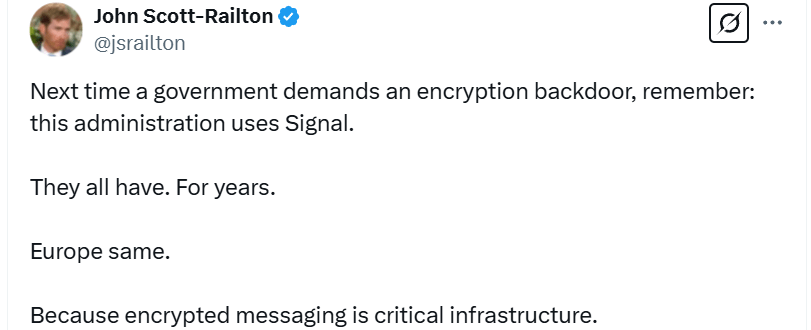

The Citizen Lab's senior researcher John Scott-Railton reacted to the exposure noting that encrypted communication apps like Signal have infiltrated all levels of communication, yet instead of recognizing it as “critical infrastructure” and supporting it for what it is, governments worldwide demand backdoors to be added to it.

The U.S. National Security Council confirmed the authenticity of the messages, calling the unauthorized inclusion of a journalist “inadvertent” and stating that a review was underway. Legal experts consulted for the Atlantic’s report warned that such use of unapproved messaging platforms could violate both the Espionage Act and federal records statutes — especially given the nature of the material and the deliberate use of disappearing messages.

While Signal itself remains secure in its design and encryption, this incident underscores the critical importance of process, policy, and user behavior in safeguarding sensitive information. Misuse of secure tools, such as adding unauthorized users, using personal devices, or bypassing official channels, can be as dangerous as using insecure platforms — if not more so, because of the false sense of security they provide.

What if the inclusion of the journalist was an intentional act done by an operative, a Biden administration worker, still employed by US government?