A targeted campaign by the North Korean Lazarus Group, dubbed Operation SyncHole, used a combination of watering hole tactics and software exploits to compromise at least six South Korean organizations between November 2024 and February 2025.

These were companies engaged in the fields of software, semiconductor manufacturing, IT, finance, and telecommunications. The campaign exploited vulnerabilities in widely used domestic software, with evidence suggesting a larger scope of impact than currently confirmed.

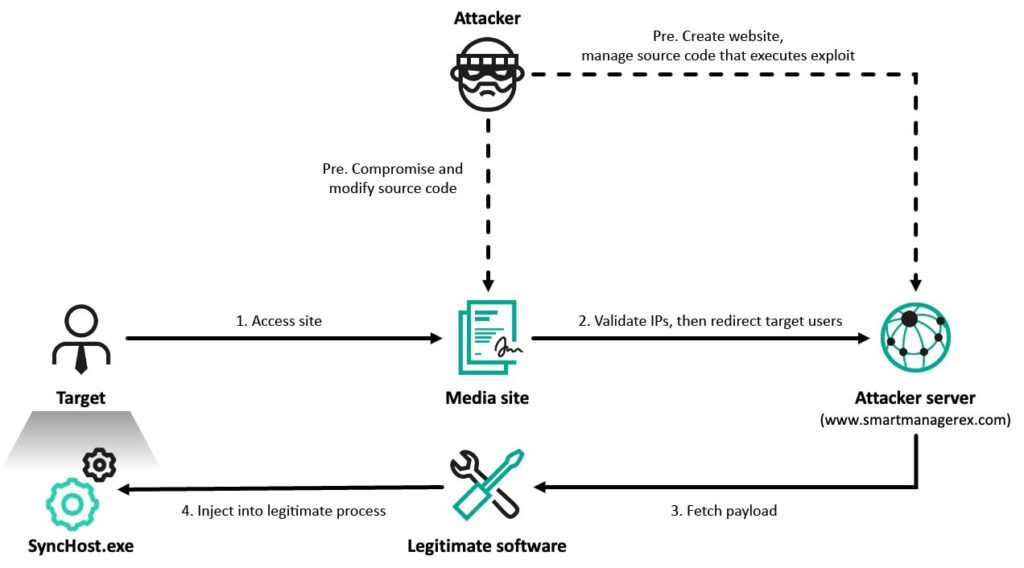

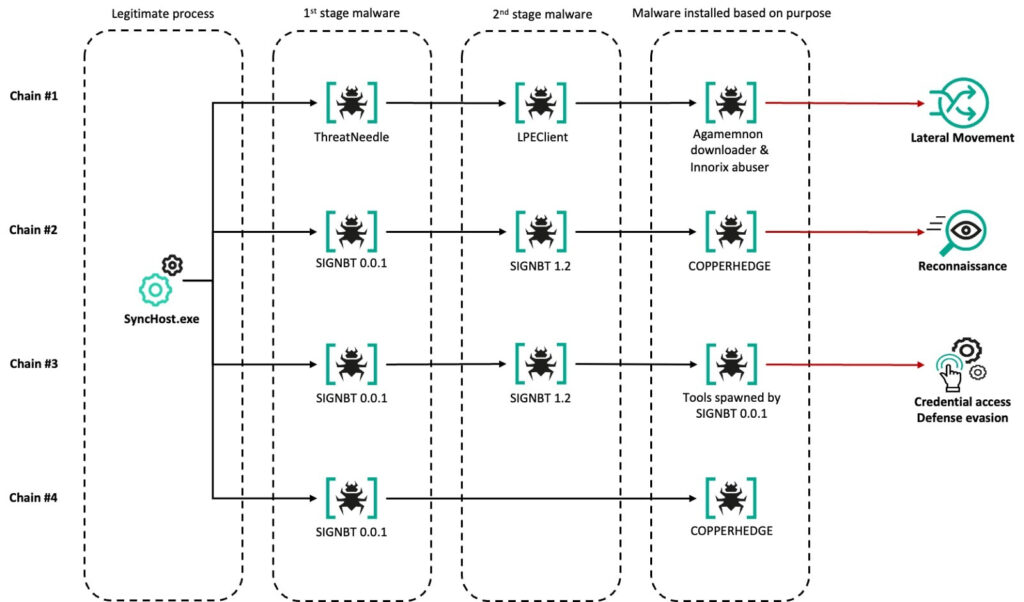

Kaspersky details a methodical two-phase attack that began with the deployment of the ThreatNeedle malware and transitioned to more advanced tools like SIGNBT and COPPERHEDGE. The operation was first observed after detecting a variant of ThreatNeedle injected into a legitimate process (SyncHost.exe) via the South Korean software Cross EX. This was followed by the exploitation of another local product, Innorix Agent, for lateral movement within networks.

Zero-day vectors

The infection chain was initiated through compromised South Korean media websites. Visitors were selectively redirected using server-side filtering scripts to attacker-controlled domains posing as legitimate services. One such domain, www.smartmanagerex[.]com, impersonated software linked to Cross EX, a component often mandated for secure online transactions in Korea. A suspected vulnerability in Cross EX was then exploited to execute malicious scripts and inject the ThreatNeedle malware into SyncHost.exe.

Cross EX is used to facilitate compatibility between security software and various web browsers in Korea. Although its method of exploitation remains unclear, forensic analysis revealed consistent execution flows and privilege escalations across infected systems.

Additionally, Kaspersky identified exploitation of a one-day vulnerability in Innorix Agent — a file transfer tool commonly installed on corporate and government machines. The attackers used a custom payload to exploit version 9.2.18.496 of the software, delivering malware across internal hosts without validation checks, and employing DLL sideloading to activate additional components like ThreatNeedle and LPEClient.

Kaspersky

Lazarus malware arsenal

The Lazarus Group deployed several well-known malware strains, each updated with new capabilities:

- ThreatNeedle, a modular backdoor, featured Curve25519-based key exchange and ChaCha20 encryption, and was split into loader and core components for stealth and persistence.

- wAgent, a downloader, used disguised DLLs and AES-128 encryption, and was capable of in-memory payload deployment via a shared object model.

- SIGNBT, deployed in versions 0.0.1 and 1.2, handled remote payload delivery and encryption via RSA and AES. The latter version included embedded configuration file paths and enhanced C2 obfuscation.

- COPPERHEDGE, a Manuscrypt variant, supported reconnaissance with 30 commands and leveraged alternate data streams for storing configuration, while communicating through randomized HTTP parameter sets.

Additionally, the Agamemnon downloader introduced Tartarus-TpAllocInject-based reflective loading, a method derived from a lineage of open-source evasion tools, highlighting the attackers' deep understanding of anti-EDR tactics.

Kaspersky

South Korea's reliance on proprietary security software for government and financial services has created an ecosystem vulnerable to local software exploitation. This dependency, combined with legacy software requirements, has been repeatedly exploited by Lazarus. Both Cross EX and Innorix Agent are commonly mandated in sectors that value high-assurance security features, making them ideal vectors for nation-state attackers seeking to blend in with legitimate software behavior.

Kaspersky's attribution to Lazarus is based on malware lineage, TTPs, and operational timestamps correlating to working hours in GMT+9. Infrastructure analysis revealed that most C2 servers were either legitimate South Korean websites that had been compromised or purpose-built domains mimicking local services. Hosting arrangements and domain reuse patterns further suggest deliberate, long-term planning by the threat actor.

Leave a Reply